活動報告

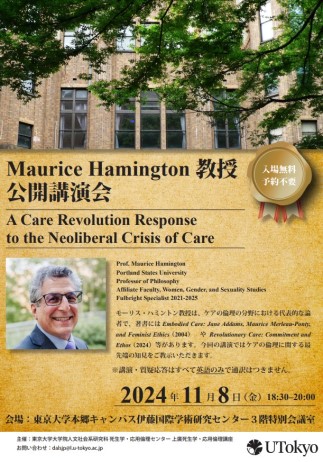

Maurice Hamington 公開講演会

"A Care Revolution Response to the Neoliberal Crisis of Care"

概要

- 日時

- 2024 年 11月 8日(金) 18:30 - 20:00

- 会場

- 東京大学本郷キャンパス 伊藤国際学術研究センター3階特別会議室

- ・「本郷地区キャンパスガイドマップ」

- ・「本郷地区バリアフリーマップ」についてはインデックスからダウンロードのうえ、ご参照ください。

参加について

※講演・配布資料・質疑応答はすべて英語のみで通訳はつきません。

- 【お問い合わせ】 東京大学大学院人文社会系研究科 死生学・応用倫理センター 上廣死生学・応用倫理講座 dalsjp[at]l.u-tokyo.ac.jp *[at]を@に入れ替えてお送りください。

講師

Portland States University

モーリス・ハミントン教授は、ケアの倫理の分野における代表的な論者で、著書にはEmbodied Care: Jane Addams, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Feminist Ethics (2004)やRevolutionary Care: Commitment and Ethos (2024)等があります。今回の講演ではケアの倫理に関する最先端の知見をご教示いただきます。

研究者向けの講演会ですが、どなたでもご参加になれます。

講演要旨

“Caring for the Revolution equals making it.”—Eva von Redecker

Despite the richness of today’s political theories of care ethics, revolution is not a subject that receives much attention. Typically associated with historical events of bloodshed and violent overthrow of regimes, the type of revolution addressed in this presentation is a methodical social and political transformation not led by generals or ministers but potentially everyone—a populist revolution of caring. On the surface, it appears audacious to claim that a care revolution is possible, particularly given the prevalent imagery of revolutions. However, I draw on the work of German feminist philosopher Eva von Redecker’s concept of “processional revolution.” Von Redecker rereads the history of revolutions to challenge the prevalent event-driven legacy and imagery. She reframes revolutions as processual and more diffuse in origin than is currently conceived. Similarly, the proposed care revolution entails a transformation of heart and mind so that we can all participate in everyday interactions that aggregate and can congeal into a social renovation. A care revolution would bring care from the margins of social value to the center through the iterative actions of individuals, groups, communities, and governments.

This presentation has three parts. The first is an explanation of care theory as a process morality. Accordingly, care is understood as a categorical moral good that we should want to commit to. Commitment is a significant term here because it suggests a personal ethical dedication rather than an imposed external system of morality. Such a commitment is not toward moral perfection but instead seeks more improvement: to be better carers. Thus, “good care” is described methodologically as skill or habit development consisting of humble inquiry, inclusive connection, and responsive action. The second part of the presentation delineates von Redecker’s understanding of “processual revolution” drawn from her historical analysis of the world’s social and political revolutions. Bringing marginalized social and political ideas to the center participates in von Redecker’s understanding of revolution. She emphasizes the fluid and dynamic nature of revolution. Part of her argument suggests that revolutions do not bring about completely novel ideas but valorize that which is familiar but not consistently well regarded. The third and final part of the presentation applies von Redecker’s analysis to care and interrogates the concept of a care revolution of bringing care to the center of personal, communal, and social life. Accordingly, the revolution is not just about a change in law or social and political practice but entails a shift in spirit along with the necessary practical changes. This revolution is not necessarily a top-down or bottom-up in impetus but a multidirectional social transformation.

Many authors address the “crisis of care,” but there are also signs of a care revolution already taking place. There is a hunger for relational approaches to the world’s problems rather than dominant neoliberal responses. The care revolution aspires to new yet familiar methods. The revolution may have already begun.